Cyril R. Gollnick, who possessed no formal engineering degree, had joined Leach in 1942. Within about one year, Gollnick produced a design which was to be sold as thePackmaster. It was an all-hydraulic rear load packer, the first models appearing in 1947. The Packmaster was the first of two landmark Gollnick designs which would ultimately catapult Leach to a position of industry leader, and radically change the state of the art in the industry as whole. Even these early Packmasters, primitive though they may be, more closely resemble the modern rear loaders of today than any of Leach’s competitors of that time. This is a lasting tribute to both Cyril Gollnick and the Leach family.

But with vision comes risk, and introducing any new product concept may often take years to mature and achieve a strong market position. At Elgin Sales, George Dodge and Andy Anderson were initially skeptical, since they already had a simple and reliable product (The Refuse Getter) which was selling better than ever. The Packmaster was bigger, heavier and more complex…and more expensive. The Refuse Getter was not abandoned, and would be available at least through the end of the 1940s, selling alongside the new Packmaster. By 1950, it was probably clear to everyone that the Packmaster was the truck of the future, and could compete toe-to-toe with the Gar Wood or any other packer.

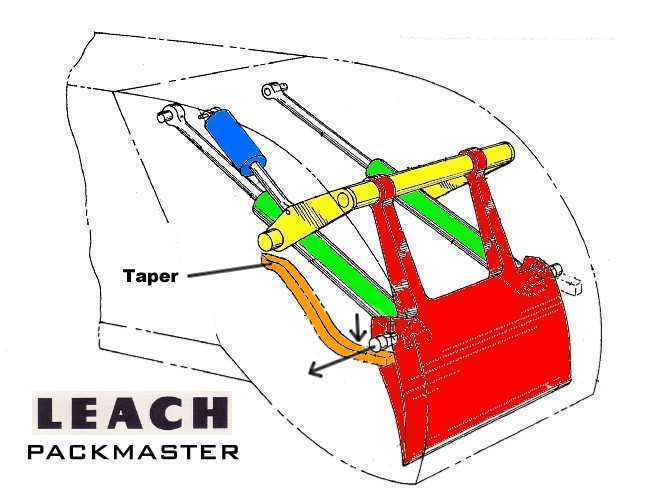

Amongst batch-loading refuse packers, Packmaster was the first to include two critical design features which are with us to this day. First, it utilized an oscillating, hydraulic powered packer panel. That is to say, the packer started from a position high in the front of the tailgate, and traveled throughout the structure to sweep and pack the refuse. Prior to this, the the school of thought on rear loaders had mostly relied on pivoting panels, as exemplified by the well-known Gar Wood and the Sicard Sanivan. The pivoting panels severely limited the hopper size to the arc of their travel, and by design necessitated that no refuse could be loaded during the packing cycle. Only after the cycle had completed, and the panels had returned to their starting position, could loading again commence. This was also true of side loaders of the era as well. But with the Packmaster method, the hopper could be reloaded at the halfway point in the cycle, when the blade started to lift and pack the refuse into the body. This was a major advance; and would lead to the industry practice of measuring reload time, which is today a common specification for refuse packers.

The other feature was a direct result of the oscillating packer blade. The Packmaster had the first truly low and deep hopper. The long hydraulic cylinders that powered the blade could “reach down” farther than the swinging panels of competitive designs. With the Packmaster, a hopper sill substantially lower than the truck frame was now a reality. Gar Wood’s Load-Packer, their biggest rival, had relatively high loading height and shallow depth, as a result of its swinging door packer panel. Sanivan was only slightly better in loading height, but added severe disadvantages in safety and was far more complex. A low hopper sill, at least among North American designs, would become another standard by which rear loaders were measured.

(Representative drawing, for illustration purpose only)

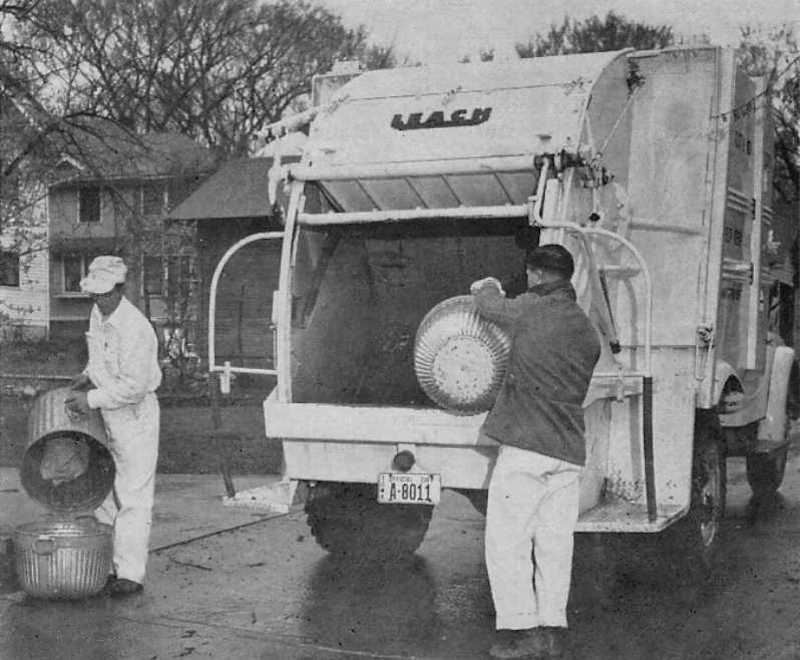

Rear view of early Iowa City Packmaster shows bi-fold door, narrow hopper width, wide riding steps and handrails

Unloading a 15-yard Packmaster; note the ‘assist’ cylinder just behind the truck cab

Leach was building a formidable distributor network, and Elgin even had an international sales division (Elinco) taking overseas orders. Onnie’s son David Leach joined the company in 1953, marking the third generation of the Leach family to come on board. Meanwhile, E.C. Leach, who had been president for over three decades, decided to sell the company in 1953. Intending to sell Leach to a competitor, he agreed instead to sell his controlling interest to his brother Onnie. By January of 1954, Onnie had completed the buy-out and became the third president of Leach Company. Elgin Sales, who had been Leach’s longtime national distributor, bought-in to the company at this time, and together they formed what would be called the Elgin-Leach company.

It turned out to be a very good move; with a solid product line, Leach was poised for growth in the next half of the 1950’s. As good a product as the Packmaster was, big changes were still to come, and it’s doubtful that even Onnie could have predicted the fantastic success Leach would enjoy in the near future.

Three big 20-yard Packmasters for Miami, Florida

And a 15-yarder for Malden, Massachusetts